Tipping Points

Dive into the science6 of the 16 Global Tipping Points

Planetary Boundaries are critical thresholds that when crossed, cause large-scale abrupt and irreversible changes occur with resulting impacts on people and nature. They were first proposed by Johan Rockström, Director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate, and a group of 28 internationally renowned scientists.

Within the Planetary Boundaries systems, certain processes exhibit Tipping Point behaviour, between different stable states. Above 1.5°C of global warming, it is very likely that we will pass multiple Tipping Points, particularly the loss of major ice sheets. And crossing one Tipping Point can increase the likelihood of crossing others - creating an irreversible “tipping cascade”.

Through this expedition, we have a unique opportunity to bring this vital science to light.

“Four of the Planetary Boundaries have already been breached. As these breaches escalate, we are likely to see social instability on a global scale”

Labrador - Irminger Seas Convection Collapse

Aerial View over Baffin Bay, Greenland.

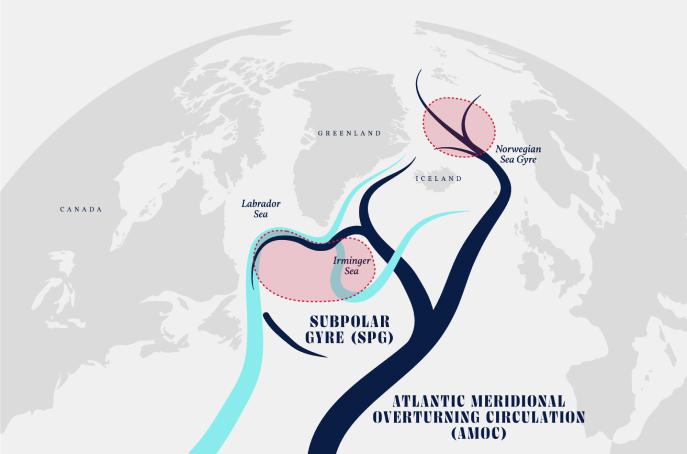

Aerial View over Baffin Bay, Greenland.In the Arctic there is an important ocean circulation called the North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre (SPG). It flows around the south of Greenland, and is linked to a deep ocean flow in the Labrador-Irminger Seas and the larger Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC).

Source: Global Tipping Points

Source: Global Tipping PointsAs ice forms from seawater in the Arctic, the salt is rejected, making the surrounding water much saltier. This dense, cold water sinks to the depths of the ocean and begins to travel South.

But this deep circulation in the Labrador-Irminger Seas is at risk of collapse. Increased precipitation and meltwater is reducing the salinity of the upper layers of the ocean - making them lighter. This, along with warming of surface layers means that this more buoyant water doesn’t sink as well as it should and the circulation weakens. Past a certain threshold, this could create a self-sustained collapse in the convection current.

Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation Cessation

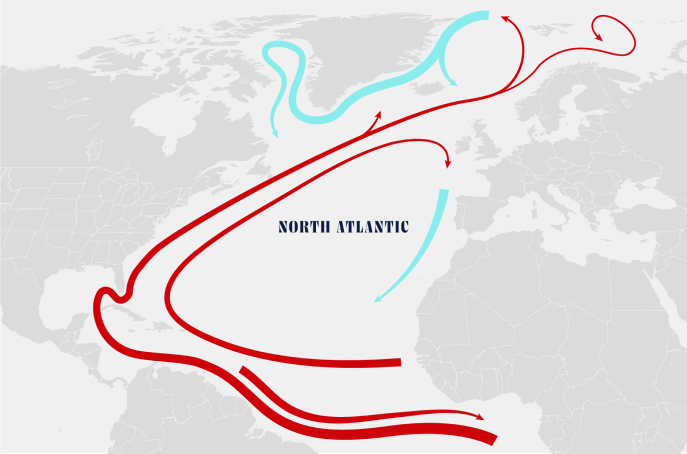

Source: Noaa, S Rahmstorf et al from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact research (PIK)

Source: Noaa, S Rahmstorf et al from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact research (PIK)The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is a system of ocean currents that brings warmer water from the tropics in the Atlantic towards the North Pole. The AMOC is a key component of the ‘global ocean conveyor belt’ which redistributes heat across the planet and mediates global warming.

The AMOC has declined 15% since 1950 and is in its weakest state in more than 1,000 years.

Current research shows that the AMOC is weakening, due to climate change - which is preventing colder waters from sinking in the Labrador-Irminger Seas. However it is unclear whether a complete collapse would occur, and when. Recent research suggests that a slow decline could lead to a sudden collapse over a period of less than 100 years.

A collapse of the AMOC would have devastating and rapid consequences across the globe. Sea level would rise by up to a metre in the Atlantic, wet and dry seasons in the Amazon would reverse, the southern hemisphere would warm and Europe would become dryer and cooler.

Greenland Ice Sheet Loss

The Greenland Ice Sheet spans an area of 1.7 million km2, covering around 80% of the surface of Greenland. It is the second largest body of ice in the world.

As global temperatures have increased, the Greenland Ice Sheet is rapidly melting. Each summer, parts of the ice sheet melt into the sea. These are normally replaced by winter snowfall. But over the past few decades, snowfall has not kept up with the rate of melting.

Greenland is losing 30 million tonnes of ice per hour

If the entire Greenland Ice Sheet melted, global sea level would rise by 7m. Current estimates for a critical threshold range from 0.8°C to 3°C of global warming, with a best estimate of 1.5°C. With less warming, models predict that the ice sheet could be reestablished. But above 2°C warming, positive feedback loops mean that the ice sheet would pass a point of no return and continue to melt, even if carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere reduced.

Arctic Winter Sea Ice Collapse

Arctic sea ice is at its maximum extent in the winter, as temperatures drop. However the maximum coverage of sea ice in the Arctic has been declining for nearly 50 years - shrinking by an area equivalent to the size of Alaska.

As more sea ice is melting in the summer months, ice in the winter must form from scratch - rather than building additional layers onto older ice. And thinner ice is more vulnerable to melting.

Winter sea ice will form in the Arctic as long as water temperature at the ocean surface drops below freezing point (1.8°C for seawater). But if the water temperature remains above freezing all year round, sea ice won’t be able to form.

Permafrost Abrupt Thaw

Thawing permafrost in Herschel Island, 2013. Boris Radosavljevic. CC-by-2.0

Thawing permafrost in Herschel Island, 2013. Boris Radosavljevic. CC-by-2.0Permafrost is ground (whether soil or rock) that has been frozen for two consecutive years or longer. In the northern hemisphere, there is around 14 million km2 of permafrost - mainly in Russia, Canada, USA, and China. The frozen ground holds huge amounts of organic material, as well as frozen methane and other gases.

The Arctic is warming four times faster than the rest of the globe, and this is leading to permafrost thawing. As this happens, the organic material begins to get broken down by microbes, releasing carbon dioxide. Previously trapped gases like methane - a greenhouse gas 28 times more potent than CO2 - are also released. Large scale thawing of permafrost would therefore lead to further warming of the planet.

Melting permafrost, Norway.

Melting permafrost, Norway.Scientists predict that globally permafrost contains around 1,400 billion tons of carbon, which is nearly double the amount already present in the atmosphere.

Thawing permafrost in Herschel Island, 2013. Boris Radosavljevic. CC-by-2.0

Thawing permafrost in Herschel Island, 2013. Boris Radosavljevic. CC-by-2.0Boreal Forest Northern Expansion

Boreal forests are found just south of the Arctic tundra, and is the world’s largest land biome. Stretching across the high latitudes in the northern hemisphere, they span Canada, China, Finland, Japan, Norway, Russia, Sweden and USA. These forests are made up of hardy species like pine, spruce, and larch. Accounting for 30% of the world’s forests, they are thought to store one third of all terrestrial carbon.

As temperatures increase, changes are occurring in the southern and northern edges of boreal forests. In the south, forests are experiencing dieback from increasing disturbances - such as drought, wildfires, and insect outbreaks. In the north, the forest is expanding into areas that were once treeless tundra. However this expansion is not compensating for the declines in the south, so overall the biome is shrinking.